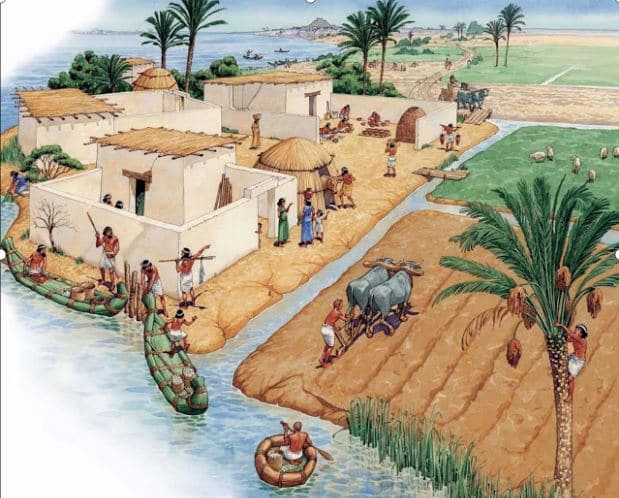

In Quimbaya, Colombia, a wife accompanies her farmer husband to measure soil fertility using simple tools. In Buton Island, Indonesia, a daughter teaches her father to manage his customers’ purchase order for his fish catches using a smartphone.[i] As a result, both households see an increase in their yield and income.

In many cases, empowering the smallholder farmers is the most important investment for the betterment of our agriculture system.[ii] They need to be constantly updated with the innovative solutions of modern farming practices. Inherently, smallholders hold the key to sustainable productivity solutions with their knowledge and wisdom. Still, in this age of climate change, introducing innovations will prepare smallholders for uncertainty.[iii] With modernized thinking, they will have better resilience.

To move forward with innovation, financial access is necessary for the smallholders. To this end, there is a rising trend — especially in the private sector — in the green investment. The term ‘green’ means that the investment is aimed for sustainability (and often by ensuring biodiversity). Not only companies but countries also aim for it. Europe’s Green New Deal might be the biggest green stimulus to date. Yet, its fund distribution still should be safeguarded and public involvement should be promoted. In fact, public-private funding provides great opportunities to ensure long-term commitment.[iv] In the Netherlands, €160 million Dutch Fund for Climate and Development is managed not only by the government but also by a consortium of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as WWF.[v] Financial resources from private and public investments are used to leverage the support in enhancing resilience to the effects of climate change, which is definitely useful for the smallholders.

Globally, G-20 countries can play a key role in this investment by allocating their revenue to provide green stimuli. Meanwhile, low middle income (LMI) countries can pivot their subsidy fund, especially those for fossil fuels, to rural development to benefit smallholder farmers.[vi] The national-level government can adhere by designing and implementing flagship policies for this systematic shift in a committed change. Even further, a fundamental change in the system would be to bring this issue to the voting booth.[vii] We cannot go back to ‘before’ not because the system is broken, but the system is what made us broken in the first place.

As with any other effort to repair a complex system, we need key ingredients to ensure the innovations and investment to reach and benefit the targets, i.e. smallholders. There are at least five ingredients [viii], as follows: 1) Tailoring the knowledge so people can easily learn, 2) Earning trust and genuine interest from the people (local buy-in), 3) Building intense and effective communication among the related multistakeholder who may have different backgrounds, 4) Securing access to investment for scaling up and out also leading the innovation, and 5) Aiming for a long term commitment from all involved parties.

Among the five points, the last is the trickiest. NGOs who spearhead field implementation know this all too well: the local government often has little autonomy and little resource at disposal, the funding from the sponsorship companies are often fragmentary as part of its Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), and election period dictates the government’s support. Therefore, a robust institutional framework needs to be established so a long-term commitment which involves the needed innovations and investment for smallholders can be sustained.

This article is part of our reflection series after participating in the Global Landscapes Forum (GLF) Bonn, which was held digitally on 2-5 June 2020.